In this article, I want to share the history of Weaviate, how the concept was born, and where we are heading towards in the near future.

A World of Wonders called Natural Language Processing

Somewhere early 2015 I was introduced to the concept of word embeddings through the publication of an article that contained a machine-learning algorithm to turn individual words into embeddings called GloVe.

Example of an embedding

squarepants 0.27442 -0.25977 -0.17438 0.18573 0.6309 0.77326 -0.50925 -1.8926

0.72604 0.54436 -0.2705 1.1534 0.20972 1.2629 1.2796 -0.12663 0.58185 0.4805

-0.51054 0.026454 0.20253 0.32844 0.72568 1.23 0.90203 1.1607 -0.39605 0.80305

0.16373 0.053425 -0.65308 1.0607 -0.29405 0.42172 -0.45183 0.57945 0.20217

-1.3342 -0.71227 -0.6081 -0.3061 0.96214 -1.1097 -0.6499 -1.1147 0.4808 0.29857

-0.30444 1.3929 0.088861

If you are new to the world of word embeddings, a metaphor to understand them is in the form of a supermarket. The supermarket itself is a space in which products are stored based on the category they are in. Inside, you can find an apple by moving your shopping cart to the right coordinates in the fruit section and when you look around you, you'll find similar products like oranges, limes, bananas, etcetera, and you also know that a cucumber will be closer by than washing powder.

This is the same way a word embedding is structured. All the coordinates combined represent a multidimensional hyperspace (often around 300 dimensions) and words that have a similar meaning are more closely related to each other, like similar products in the store.

Being able to represent words in a space gives you a superpower, because it allows you to calculate with language! Instead of creating algorithms to understand language, it is now possible to simply look up what is in the neighborhood in the space.

How to semantically store data objects

While working on software projects in my day-to-day life, I noticed that one of the most recurring challenges presented itself in naming and searching. How would we call certain objects and how could we find data that was structured in different ways? I fell in love with the semantic web but the challenge I saw there, was the need to have people agree on naming conventions and standards.

This made me wonder, what if we wouldn't have to agree on this any more? What if we could just store data and have the machine figure out the concept that your data represents?

The validation of the concept was chunked up into three main sections that were validated one by one.

- Can one get more context around a word by moving through the hyperspace? If so;

- Can one keep semantic meaning by calculating a centroid of a group of words (e.g., "thanks for the sushi last week")? If so;

- Can this be done fast without retraining the ML model?

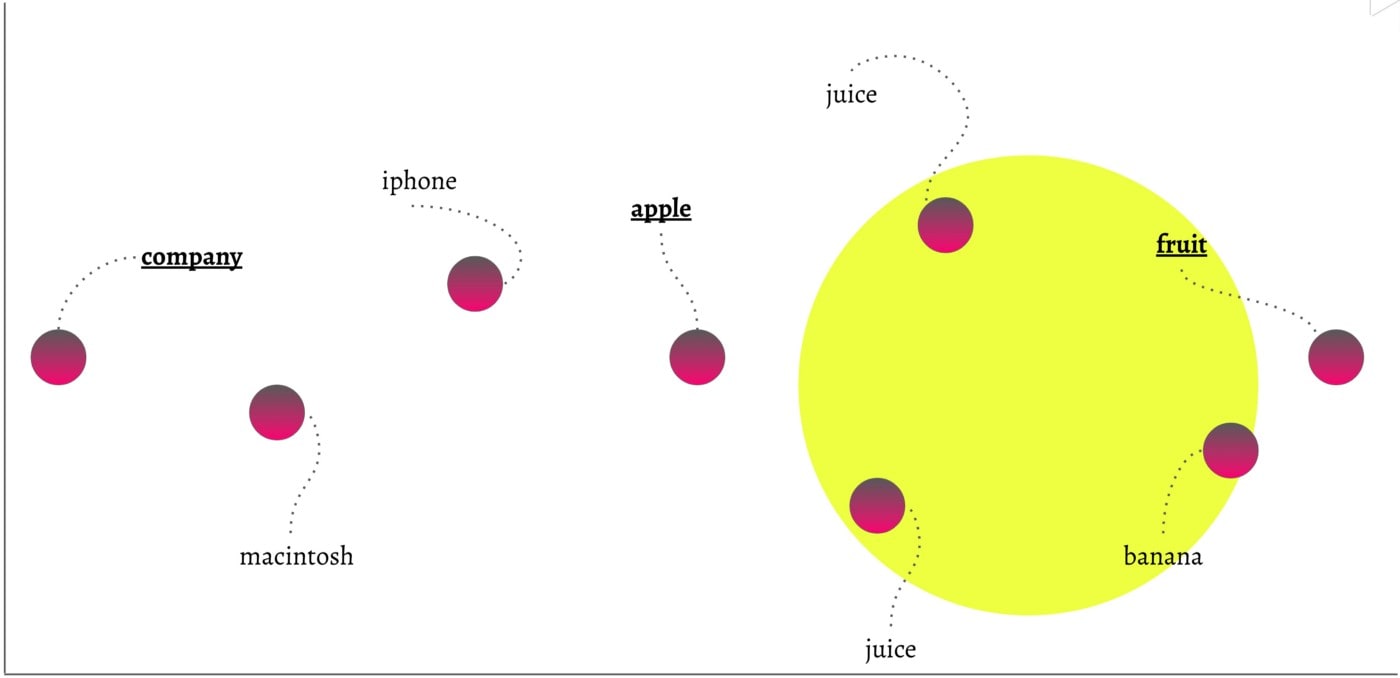

Finding more context around a word has to do with a concept called disambiguation. Take for example the word "apple". In the hyperspace, if you look for other words in the neighborhood, you will find words related to apple the fruit (e.g., other fruits, juices, etcetera) but also Apple the company (iPhone, Macintosh, and other concepts related to the company).

To validate if we could disambiguate the word "apple" the following simple step was taken. What if we looked for all the words that are in the neighborhood of the space in between "apple" and "fruit"? Turns out the results are way better! We can disambiguate by moving through the hyperspace while using individual words as beacons to navigate.

In the next step, the goal was to validate if we could keep semantic meaning when storing a data object in the hyperspace by calculating the centroid using the individual words as beacons. We did that as follows, the title of this Vogue article: "Louis Vuitton's New Capsule with League of Legends Brings French High Fashion to Online Gaming — and Vice Versa".

If we look up the vector positions for the individual words (Louis, Vuitton, new, capsule, etc.) and place a new beacon in the center of the space of those vector positions, can we find the article by searching for "haute couture"? This turns out to work as well! Of course, through time, the centroid calculation algorithm in Weaviate has become way more sophisticated, but the overall concept is still the same.

By validating the above two assumptions, we knew that we could almost instantly store data objects in a semantic space rather than a more traditional row-column structure or graph. This allows us to index data based on its meaning.

Although we had validated the assumptions of the semantic concepts, it was not enough to create an actual semantic search engine. Weaviate also needed a data model to represent these results.

Things Rather Than Strings

In September 2017 I wrote a blog post about the overlap between the internet of things and the semantic web. IoT focuses on physical objects (i.e., "things") and the semantic web focuses on the mapping of data objects that represent something (a product, transaction, car, person, etcetera) which at the highest level of abstraction, are also "things".

I wrote this article because, in January 2016, I was invited as part of the Google Developer Expert program in San Francisco, to visit the Ubiquity Conference. A conference where, back then, Google's Weave and Brillo were introduced to the public.

Weave was the cloud application built around Brillo, but it piqued my interest because it focused on "things", how you defined them, and actions that you could execute around them. The very first iteration of Weaviate focused on exactly this: "Could Weave be used to define other things than IoT devices like transactions, or cars, or any other things?". In 2017 Google deprecated Weave and renamed Brillo to Android Things but the concept for Weaviate stayed.

From the get-go, I knew that the "things" in Weaviate should be connected to each other in graph format because I wanted to be able to represent the relationships between the data objects (rather than flat, row-based information) in an as simple and straightforward manner as possible.

This search led to the RDF structure used by schema.org, which functioned as an inspiration for how to represent Weaviate's data objects.

Weaviate is not per se RDF- or schema.org-based, but is definitely inspired by it. One of the most important upsides of this approach was that we could use GraphQL (the graph query language which was entering the software stage through Facebook open-sourcing it) to represent the data inside Weaviate.

With the concept of realtime vectorization of data objects and RDF-like representation of Weaviate objects in GraphQL, all the ingredients to turn Weaviate into the search graph that it currently is, were present.

The Birth of the Weaviate Search Graph

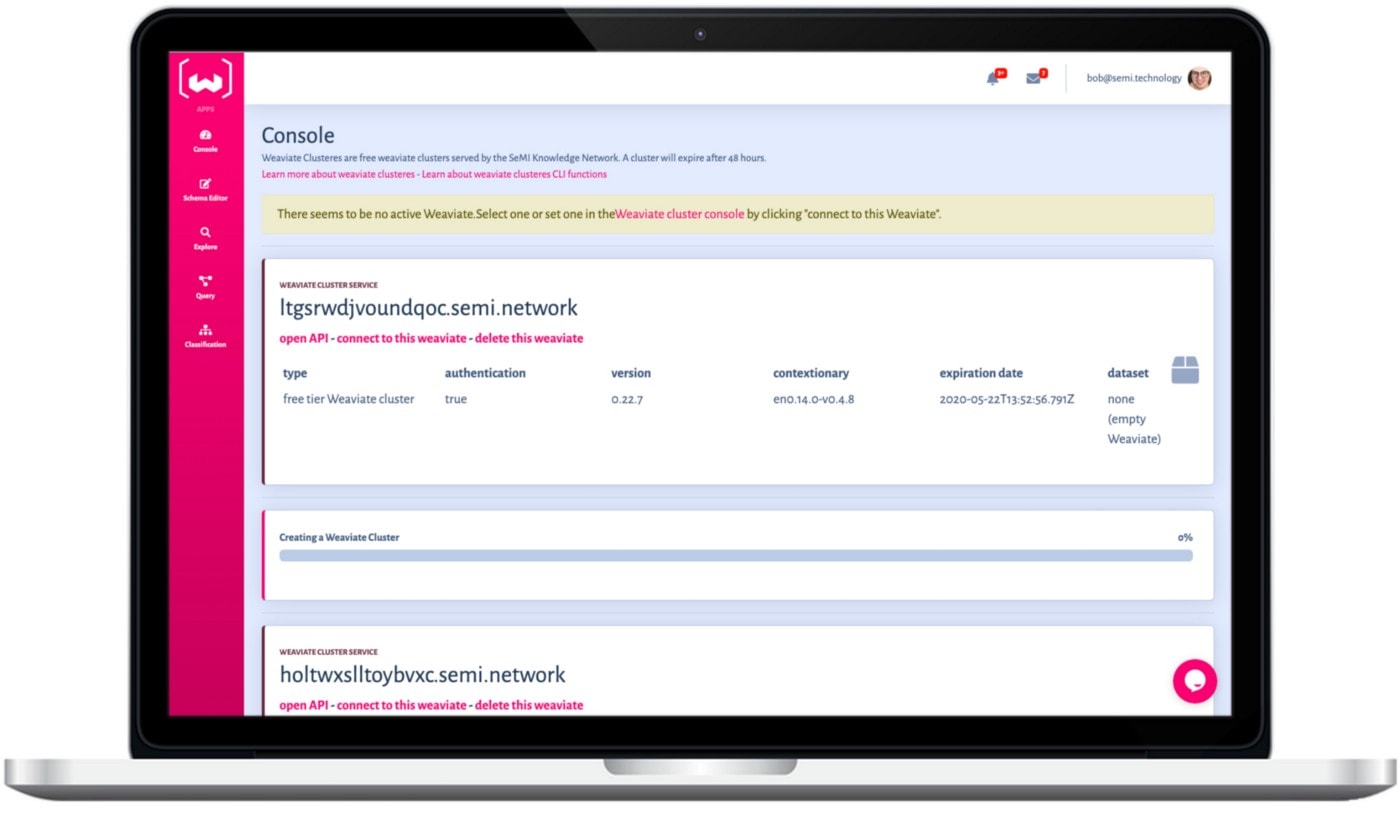

By the end of 2018, I entered Weaviate into a startup accelerator program in The Netherlands. A place where I had the time to build a team around Weaviate that could help get the software to production and create a business model around the open-source project (the startup became: SeMI Technologies, which is short for Semantic Machine Insights).

When the team started, Weaviate was more of a traditional graph where the semantic (NLP) element was a feature rather than the core architecture. But when we started to learn how powerful the out-of-the-box semantic search was and the role that embeddings play in day-to-day software development (i.e., a lot of machine learning models create embeddings as output), the team decided that we wanted to double down on the NLP part and vector storage, creating a unique open-source project, which could be used as a semantic search engine. The Weaviate Search Graph was born.

How people use it today

One of the coolest things about an open-source community and users of the software is to see how people use it and what trends you can see emerge around implementations. The core features of Weaviate are the semantic search element and the semantic classification, which are used in a variety of ways and industries.

Examples of implementations include: classification of invoices into categories, searching through documents for specific concepts rather than keywords, site search, product knowledge graphs, and many other things.

The Future

Weaviate will stay fully open source for the community to use. The team is growing to accelerate building Weaviate and supporting users. We are releasing new features very frequently, like new vector indexes and search pipeline features, and Weaviate Cloud and Weaviate Query App.

Listen to Bob's story at the Open Source Data

Want to learn more about the background of Vector Search and how the ecosystem is developing? Listen to Sam Ramji from DataStax interviewing Bob van Luijt about Vector Search and the AI stack..

Ready to start building?

Check out the Quickstart tutorial, or build amazing apps with a free trial of Weaviate Cloud (WCD).

Don't want to miss another blog post?

Sign up for our bi-weekly newsletter to stay updated!

By submitting, I agree to the Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.