If you're interested in where memory is heading at Weaviate, sign up for a preview today.

Memory is a term you've probably been hearing like a steadily increasing drumbeat over the last year. This is for good reason – many of 2024 and 2025's PoC's have graduated and become full-fledged, mission-critical production applications. And with that an interesting problem has emerged, and it's not one that can be solved by today, or tomorrow's LLMs. Not because models aren't capable, but because this is fundamentally a systems problem and not a model limitation.

What we're running into is the infinite loop the user and the system (read: the LLM embedded in an application) find themselves stuck in. A loop created by the absence of one critical trait: continuity.

I Am A Limited Loop

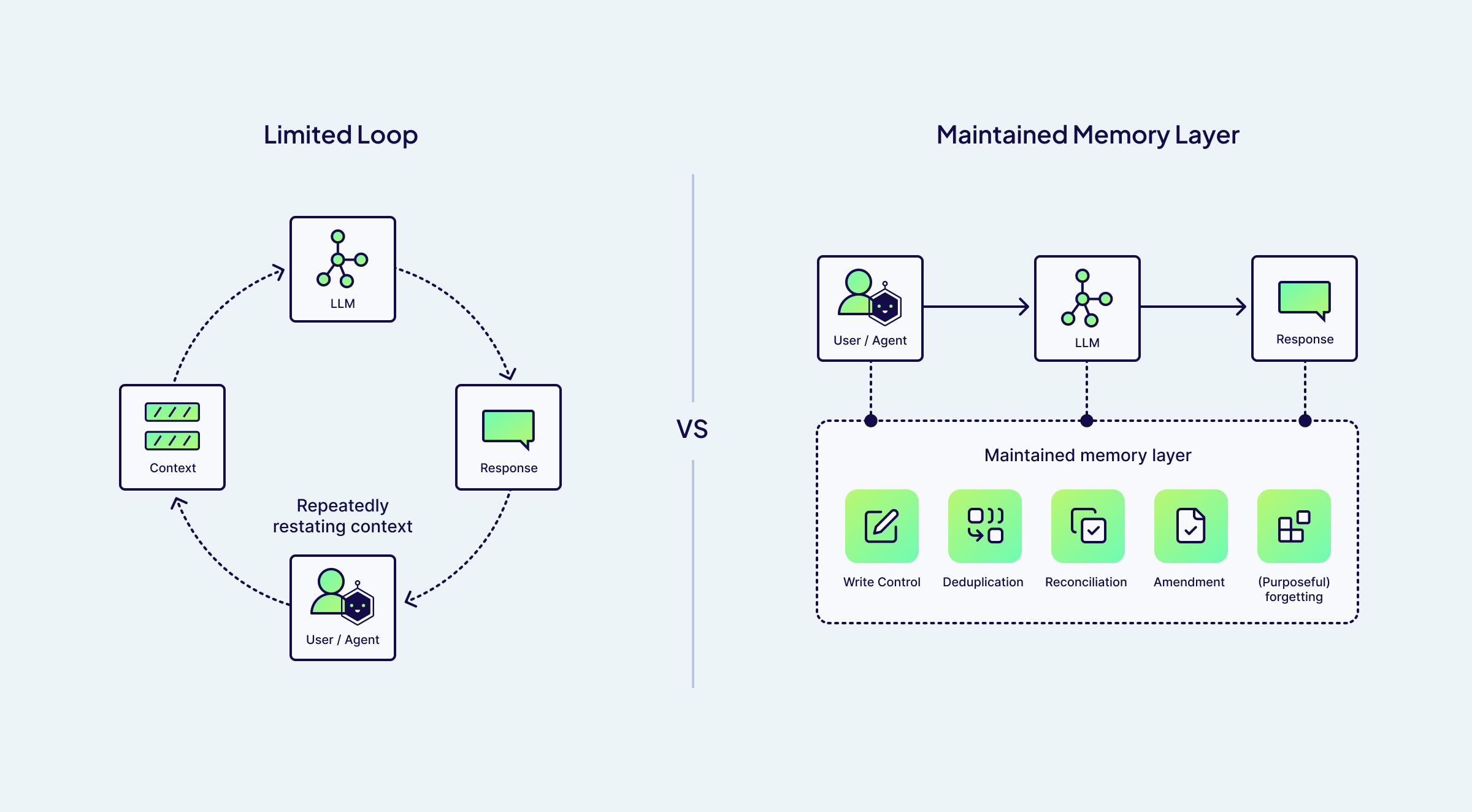

Today's AI applications operate in what might be called a limited loop, where each interaction is treated largely as disposable, bound to a single session and with incidental carryover between sessions. For those of you who have used chat-based LLMs without memory, some of these frustrating loops may already feel familiar. You might have a particular preference for how you want information to be presented, or simple facts about yourself like your name, where you live, what your favorite foods are. Personally, I like it when complex or unfamiliar topics are explained simply at first, and only then do I want the deep dive.

But the content of these loops goes beyond preferences. It might be a particular overarching goal you have for a period of time: maybe you are learning to knit this year, gradually gaining more skill across a series of interactions; or maybe you're working on a complex coding project that spans many chats, with specific technical decisions important to your specific project. In both cases, your context accumulates over time. And in both cases you find yourself restating and refreshing said context again and again just to get the system to "play ball".

This lack of continuity across sessions and over time brings us to the limit of the loop: the point where the act of this repetition becomes more costly than the value you get from the system itself.

The cost of the limited loop

So far we have framed the user in this loop as a human, but increasingly this is not the case. More and more, the user is itself an agent, usually with a fixed directive such as customer service, sales qualification, or code generation.

In the case of agents, the limited loop problem intensifies. Agents operate continuously, carry out tasks concurrently, and consume and produce information faster than any human ever could. Without continuity, they hit the limits of the loop exponentially faster, repeatedly re-deriving the same conclusions, regenerating near-identical facts, and discarding half-baked products. What looks like forgetfulness at human scale becomes churn at machine scale, with duplicated work, conflicting intermediate states, and an ever-growing pile of partially useful results.

A few years ago, the answer to this problem may have been to fine-tune a model, or for a large enough domain, to retrain one completely. Today, this mentality is impractical, not only because of astronomical costs associated with training, but more importantly because underlying information is changing rapidly. A model fine-tuned on last month's financial news becomes a relic very quickly.

Modern models are exceptional generalizers. Given the right information at the right time, they can learn to use tools and solve problems they've never encountered before. That's why, for agents, memory and continuity aren't nice-to-haves; they're absolute requirements for any system expected to operate over time and adapt as circumstances change.

From human friction to systemic failure

At its heart, "memory" (or context engineering, or knowledge management—pick your poison) is conceptually simple, so don't let any glossy marketing page convince you otherwise! Given an input – conversational data, strings, or a user event – a memory layer will query a data store, return some facts, and inject them into the context of the application so the application's underlying model(s) can respond primed with those facts. The hard part isn't the idea; it's getting this to work reliably over time.

Memory, for both humans and computers, is an ability that needs to survive time. Memories accumulate through time, and time itself introduces drift: facts change, preferences evolve, and information contradicts or duplicates. Implemented naively, memory doesn't just grow but also decays.

Imagine a weekend prototype for memory. Facts are embedded and stored as they arrive, later retrieved and injected back into prompts as context. Rinse and repeat.

At first it feels like magic. Continuity appears. Personalization works. The agent suddenly seems to "know" things it didn't before. For a moment, it looks like the memory problem is solved.

But as the drumbeat of time continues, cracks start to show. Responses get slower as more context is stuffed into every prompt. Worse, the answers start to drift wildly, as the model randomly pulls from conflicting or outdated information as all retrieved facts look equally plausible. And because agents produce and consume information faster than any human ever could, they reach this failure mode much sooner. What might take months to break a human-facing system can take days or hours for an agent operating continuously.

The result isn't just inefficiency, but confusion. A real world example helps make this concrete. Imagine a developer-facing agent. Early in a project, it recommends a specific library version or deployment pattern. Months later, the underlying tooling has changed, but the old guidance is still sitting in memory, so the agent confidently suggests instructions that are no longer correct and leaves the user worse off than if they hadn't asked at all.

This is the failure mode of naive memory. What starts off as helpful continuity slowly turns into accumulated noise. Without active maintenance, memory becomes an ever-growing pile of notes, some useful, some stale, and some flat-out wrong, and the system has no principled way to tell the difference.

Memory isn't stored, it's maintained

This is why memory isn't something you simply store. It's something you have to actively maintain. A useful memory system behaves like a custodian for context: it quietly manages the plumbing and lifecycle of what's remembered so the system remains coherent over time.

These custodial duties include:

Write Control: what to store, when to store it, and at what confidence. Not every interaction deserves to become a memory. A passing comment, speculative answer, or unverified assumption should not be treated the same as confirmed preference or durable decision. Good write control prevents noise from becoming fact.

Deduplication: collapsing repeats and near-repeats into a single canonical fact. If a user mentions their preferred format ten times a day in ten different ways, the system shouldn't remember ten slightly different versions. It should remember one stable preference and not a growing pile of paraphrases.

Reconciliation: handling contradictions and drift as reality changes. People change and systems evolve. What was true last month may no longer be true today. A memory system needs to recognize when new information supersedes old information instead of blindly preserving both.

Amendment: correcting a wrong fact rather than just appending newer versions. If the system learns something incorrect, such as a wrong address or outdated configuration, it shouldn't bury the correction under layers of history. The incorrect fact should be amended and not merely outvoted.

(Purposeful) forgetting: retention, deletion, and expiry as first-class operations. Some information is only relevant for a short term. Temporary goals and transient context should naturally fade away. Forgetting isn't a failure of memory but a requirement for keeping memory useful.

Without these mechanisms, memory becomes an ever-growing pile of notes. With them, it becomes a maintained state that's useful and trustworthy at any scale.

When Memory becomes Infrastructure

Infrastructure is what the rest of your system depends on implicitly. You don't "use" it in one place. Instead, it quietly shapes reliability and functionality across your stack. When it fails, the failure propagates and is felt across your entire application. Memory looks like infrastructure for a simple reason: it is inseparable from storage. The moment you expect continuity over time, you're committing to storing state efficiently, retrieving it quickly, and enforcing strong guarantees around tenancy and isolation.

Once memory is relied upon in real workflows, it stops behaving like a feature and starts behaving like a dependency. This is especially true for agents that depend on memory for continual learning. For these agents memory is what ensures they adapt and improve over time while staying resilient to drift or changes in an underlying system. Memory relies on the same properties we expect from the data layer itself: predictable performance at scale, hard boundaries between users and projects, permissions that are enforced rather than implied, and retention and deletion policies that actually take effect.

These are not application-layer conveniences or concerns, they are storage layer guarantees. Baking memory into the storage layer enables it to inherit the same isolation, durability, and operational guarantees as the system of record it's built on.

What memory means for Weaviate

With that framing, the question becomes practical: what does "memory as infrastructure" require from the systems we build? At Weaviate, we're approaching memory as a first-class data problem, designed to be durable, governable, and safe under change. That leads us to a few guiding principles.

These tentpoles we'll be using here at Weaviate as we build memory from the ground up, not just to store context, but to orchestrate behaviour, ground decisions, and allow systems to evolve safely over time:

- Memory must be durable, but not permanent

- Memory must be curated, not simply accumulated

- Memory must be programmable, not prescriptive

- Memory must resolve reality, not preserve history

- Memory must scale with time

- Memory must be able to adapt to new

Built upon these guidelines, memory becomes the maintained state that agents can rely on as they independently operate, coordinate work, and adapt continuously to a changing world. These are the standards we are holding ourselves to, and we are excited to have all of you along for the ride.

If you're interested in where memory is heading at Weaviate, sign up for a preview today.

Ready to start building?

Check out the Quickstart tutorial, or build amazing apps with a free trial of Weaviate Cloud (WCD).

Don't want to miss another blog post?

Sign up for our bi-weekly newsletter to stay updated!

By submitting, I agree to the Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.