Intro

There is a lot of excitement around Deep Learning systems with new ML models being trained every day. However, they have been limited by the need for large labeled datasets, which leads us on a search for other solutions that could help us avoid that limitation.

We found interesting ideas in the Learning to Retrieve Passages without Supervision paper by Ori Ram, Gal Shachaf, Omer Levy, Jonathan Berant and Amir Globerson. The authors explore Self-Supervised Learning – a class of learning algorithms that can bootstrap loss functions – as an alternative route to training new models without the need for human labeling!

Self-Supervised Learning has led to massive advances in generative modeling and representation learning. In this article, we will explain Span-based Unsupervised Dense Retriever (Spider), a recent breakthrough for Self-Supervised representation learning applied to text retrieval in search.

Results

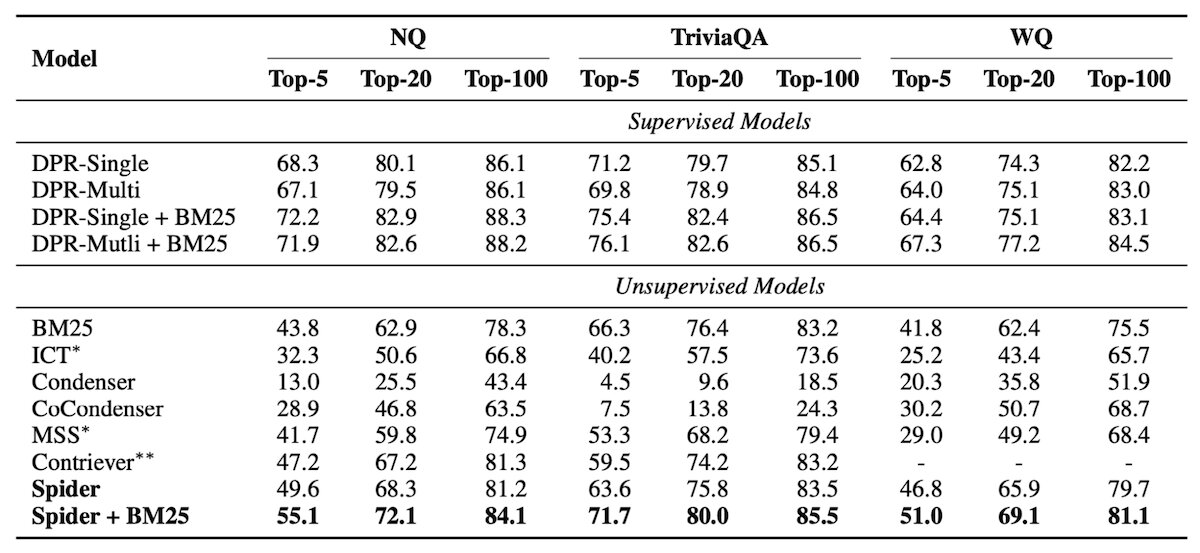

The results Spider achieves are extremely exciting! The headline is that Spider's Zero-Shot Generalization rivals the performance of the Supervised baseline on Supervised evaluation. This means that we take the labeled dataset, divide it into train-test splits, train a Supervised model on this train split, and then evaluate both models on the held-out test split. Although Spider has not been trained on this distribution (Zero-Shot Generalization), it achieves a similar performance to the model which has!

The authors further probe this Zero-Shot Generalization across several Open-Domain Question Answering datasets to illustrate how much better these Self-Supervised algorithms are than their Supervised predecessors. Further, the authors show how we can target Spider’s performance to a particular data distribution with Transfer Learning. The new algorithms prove to be much more sample-efficient, requiring only 128 labeled examples!

Information Retrieval with Deep Learning

Information Retrieval describes the task of matching a query with relevant information in a large collection of documents. For example, the question "What is the atomic number of oxygen?" would be paired with the Wikipedia sentence "Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8".

In order to answer queries based on data from Wikipedia, we take every sentence, or paragraph from Wikipedia, and use a Deep Learning model to build a predicted vector representation. Before we can use the Deep Learning model for this, we need to first train it! And in order to train a Deep Learning model, we need:

- a dataset (such as paragraphs from Wikipedia),

- and an optimization task.

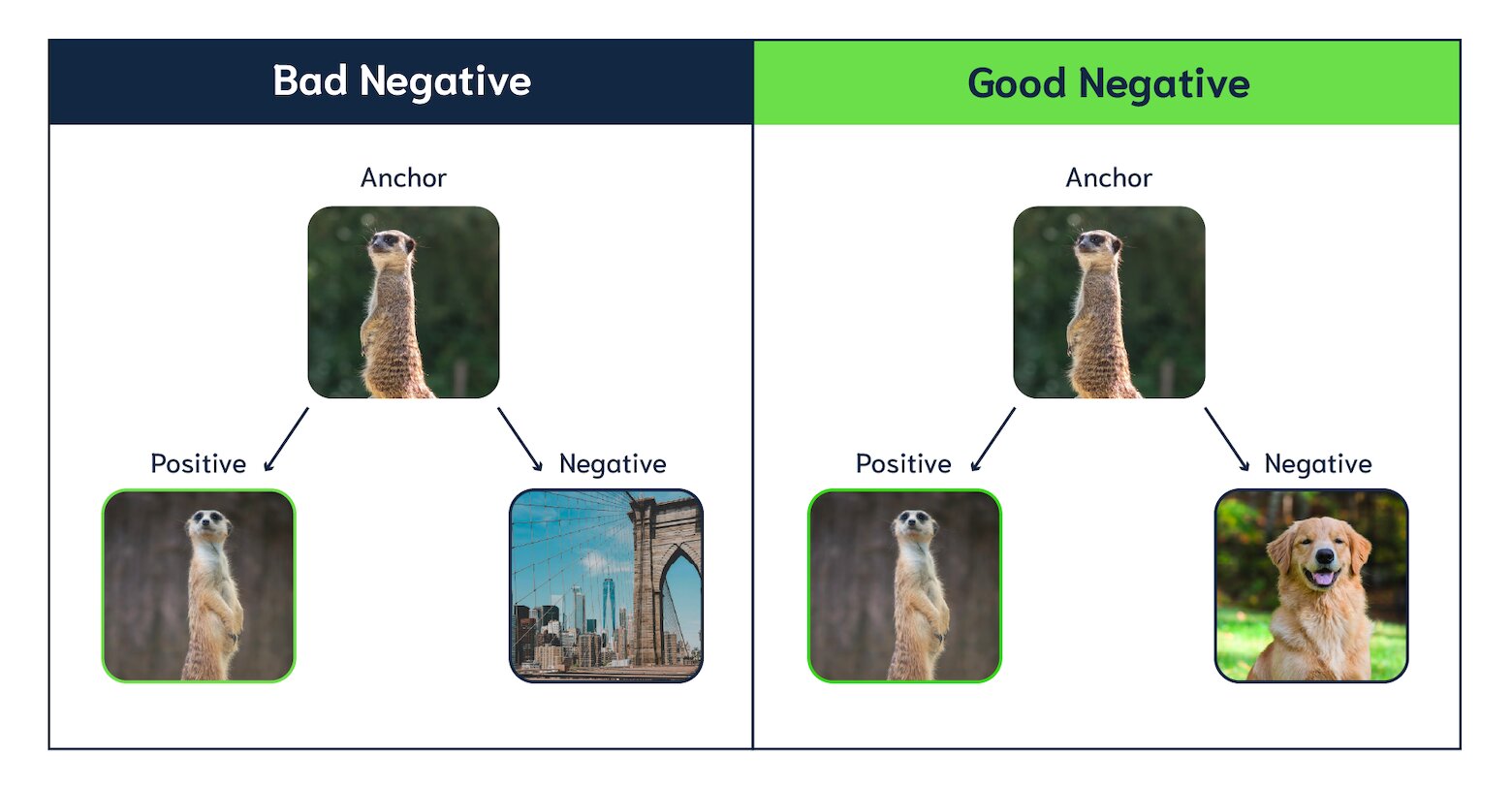

Here we can use Contrastive Learning, which is a strong optimization task. Contrastive Learning uses a combination of positive (semantically similar – we want these to match) and negative (semantically dissimilar – we don't want these to match) samples from a given anchor/query point.

The image below illustrates the concept of Contrastive Learning. We want to align representations of Meerkat images by contrasting them with sampled negatives. If we choose negatives that are too easy (like comparing Meerkats with a New York City photograph), the model won't learn a whole lot about semantics. However, if we choose a better negative (like a Golden Retriever), the model has to capture more semantics about the visual features of Meerkats.

Images sourced from Unsplash – Thanks to Bastian Riccardi, Dan Dennis, Clay Banks, and Shayna Douglas!

Images sourced from Unsplash – Thanks to Bastian Riccardi, Dan Dennis, Clay Banks, and Shayna Douglas!

The problem with Contrastive Learning is that the construction of positive and negative samples typically requires expensive and time-consuming manual labeling. Self-Supervised Learning, on the other hand, aims to minimize this cost and offers a clear breakthrough in the performance of these techniques.

Some quick terms before diving in:

- Anchor - A query point that the model takes as input to compare with the Positive and Negative.

- Positive - The data point we want the model to predict is semantically similar to the Anchor.

- Negative - The data point we want the model to predict is semantically dissimilar to the Anchor.

- Document - A collection of Passages such as a Wikipedia article, blog post, or scientific paper, to give a few examples.

- Passage - 100 word chunks extracted from a Document.

- Span - A snippet of words such as "Deep Learning" or "biological brain of most living organisms".

- Recurring Span - A piece of text (ignoring punctuation, etc) that appears in more than one Passage.

What’s New - Span-based Unsupervised Dense Retriever (SPIDER)

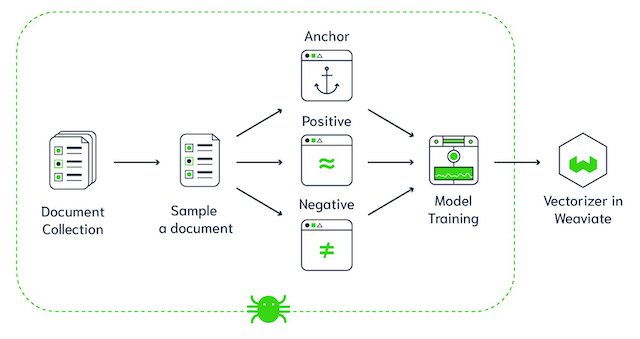

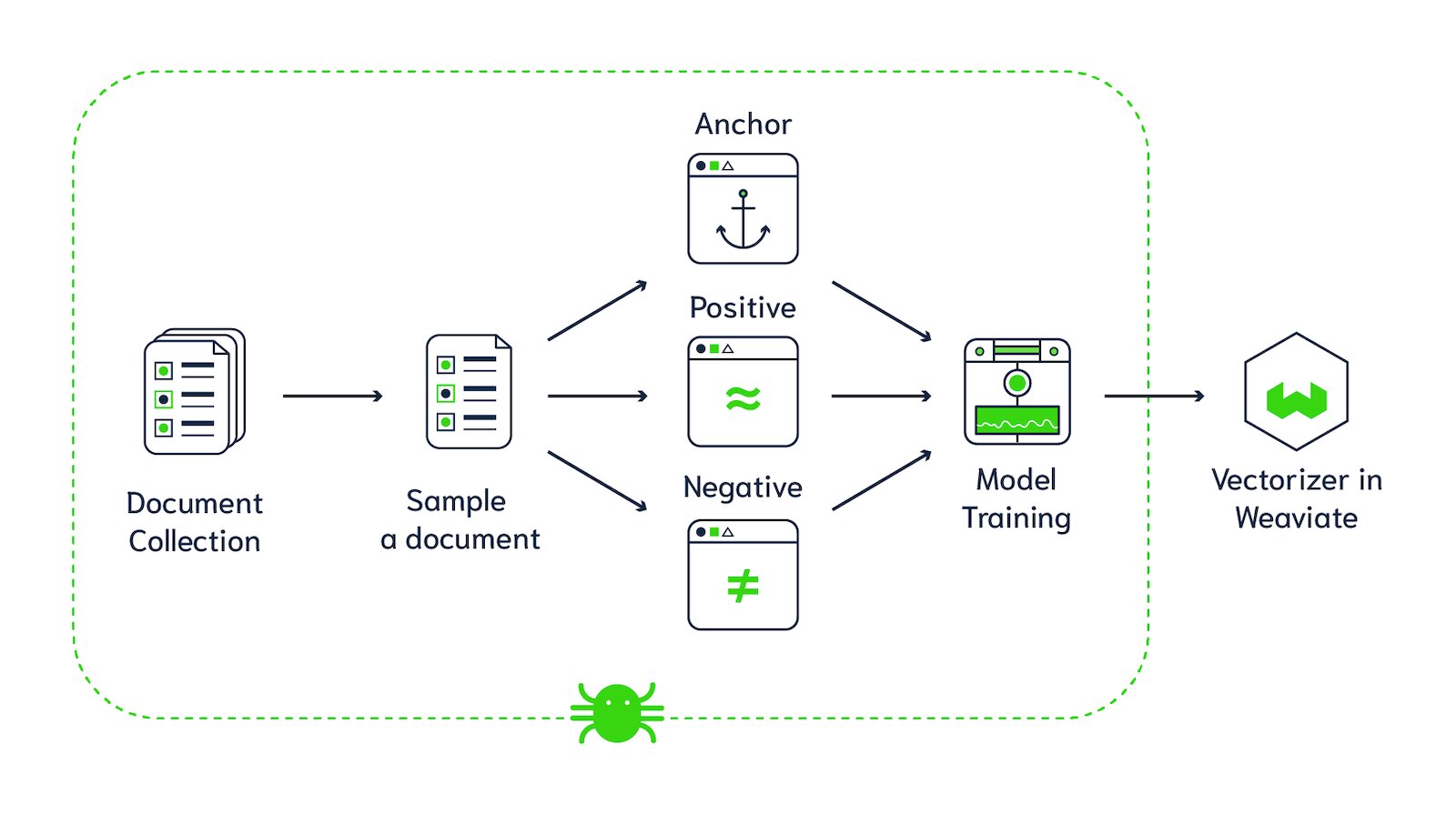

Spider offers a way to automatically generate Anchor, Positive and Negative training data with Recurring Span Retrieval. One of the key elements of Spider is to identify the longest Recurring Spans that appear in two (or more) different places within the same Document. Then use that to later construct positive and negative training data.

Exercise – Spider implementation

As an exercise, I've prepared a Google Colab notebook, where I implemented a basic version of the Spider Algorithm. The idea is to identify the longest Recurring Spans in the "Deep learning" Wikipedia article.

Exercise – pseudocode

In case you are curious on how my implementation works. I can explain it in 4 steps:

Step 1 – Split the Document in a list of 100 word Passages.

Note. We could also eliminate punctuation and stop words.Step 2 – Extract spans (n-grams) from all Passages.

For example, from the sentence: "Deep learning (also known as deep structured learning)..."

we could get the following 3-grams / spans:

["Deep learning also", "learning also known", "also known as", "known as deep"]Step 3 - Find matching Recurring Spans across Passages.

This can be done with a double loop where you go through the n_grams of a passage and then compare it to the set of n_grams in every other passage.Step 4 - Find the longest Recurring Spans.

Finally, sort Recurring Spans by length and take the longest matching passages to use as an Anchor and Positive pair.

Exercise – results

As a result, the algorithm identified the following, as the longest Recurring Span in the "Deep Learning" article:

"and toxic effects of environmental chemicals in nutrients, household products and drugs"

With that we can construct an Anchor, Positive & Negative samples, like this:

Anchor = "Research has explored use of deep learning to predict the biomolecular targets, off-targets, and toxic effects of environmental chemicals in nutrients, household products and drugs."

Positive = "In 2014, Hochreiter's group used deep learning to detect off-target and toxic effects of environmental chemicals in nutrients, household products and drugs and won the "Tox21 Data Challenge" of NIH, FDA, and NCATS."

Negative = "Advances in hardware have driven renewed interest in deep learning. In 2009, Nvidia was involved in what was called the "big bang" of deep learning, "as deep-learning neural networks were trained with Nvidia graphics processing units (GPUs)."

Exercise – summary

It was a fun exercise seeing which spans re-appeared in the "Deep Learning" wikipedia article such as "toxic effects of environmental chemicals in nutrients household products" or "competitive with traditional speech recognizers on certain tasks".

Feel free to open my Google Colab notebook, and replace the Raw_Document text with the text of your document of choice! It will be interesting to see what you get.

SPIDER – deeper dive

The notion of passages is a clever Self-Supervised Learning trick that uses the structure inherent in documents such as Wikipedia articles. A passage is the abstraction of atomic units, i.e. sentences, paragraphs, or some arbitrary sequence length. Passages are sourced from documents such as the Wikipedia article "Oxygen". Thus positive pairs are passages that share an overlapping n-gram and negative pairs are passages that do not.

This has an auto-labeling benefit since the negative pair is likely to be semantically similar to the query point, rather than learning the function of entailment which distinguishes positives and negatives. Similar to the image above, which either compares a Meerkat with a New York City photograph or a Golden Retriever, we want to find better negatives for text retrieval. We will get better representations if the model learns to contrast particular sections of the "Oxygen" article, rather than something describing the basketball career of LeBron James.

Query Transformation

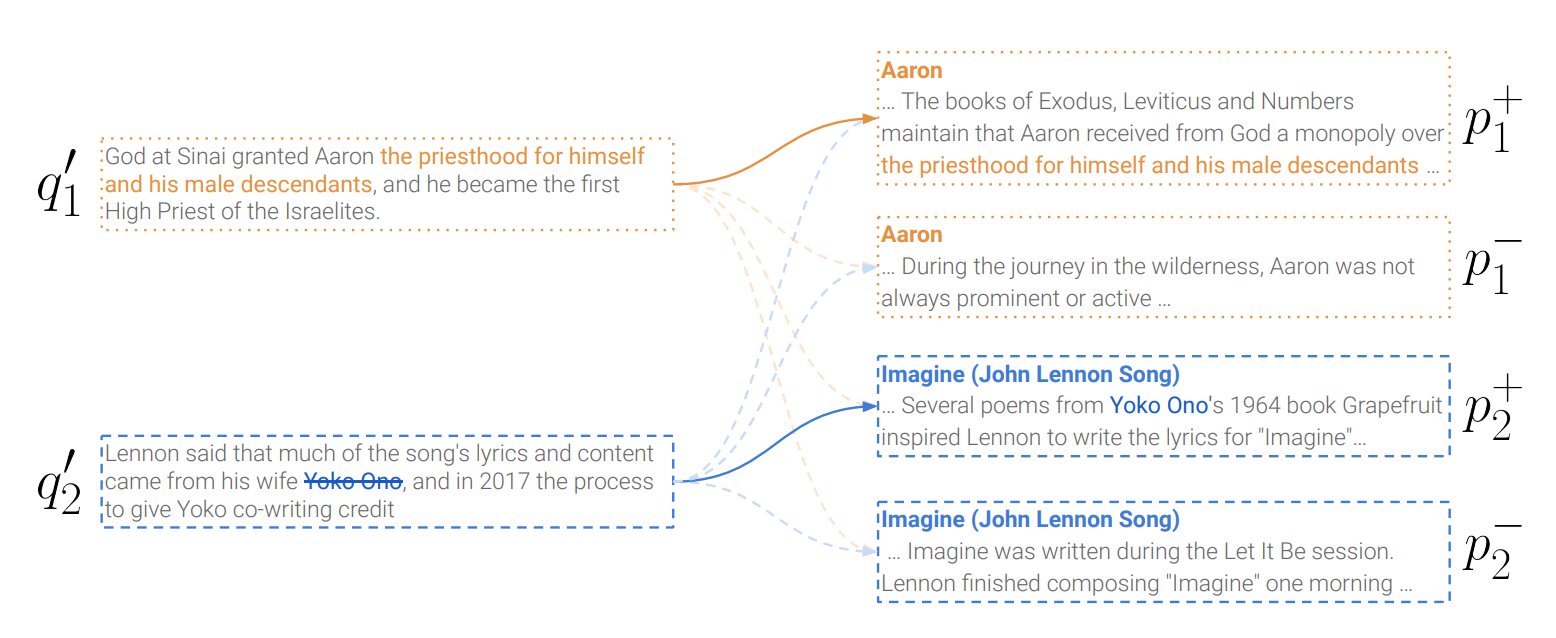

Thus far, we have presented 2 key innovations in Spider – Recurring Span positive selection and Document-Passage decomposition to leverage the inherent structure in a Document to source anchor, positive, and negative data tuples for Contrastive Learning. The third key innovation we will explore is Query Transformation.

Once positive pairs are sampled based on Recurring Spans, a Query Transformation is either applied to the anchor or not, with 50% probability. If not applied, the anchor remains as it was found in the text. Alternatively if the query transformation is applied, the overlapping n-gram is deleted from the anchor passage. The anchor is further processed via adjacent window sampling of random length between 5 and 30 neighboring tokens. This is done to make the anchor better represent the queries we expect to see with search systems, which generally have shorter length than the passages they aim to retrieve.

The authors experimentally ablate the effectiveness of applying this query transformation, the impact of sampling a negative as well as a positive (i.e. using positives from other documents as negatives for the current query point), as well as the impact of batch size and training time on performance.

The image below demonstrates two examples with the matching Recurring Spans "the priesthood for himself and his male descendants" and "Yoko Ono". The first anchor point keeps the Recurring Span in the positive. The second anchor deletes the phrase "Yoko Ono".

Image source: Learning to Retrieve Passages without Supervision, Ram et al. 2022.

Image source: Learning to Retrieve Passages without Supervision, Ram et al. 2022.

Experimental Evaluation

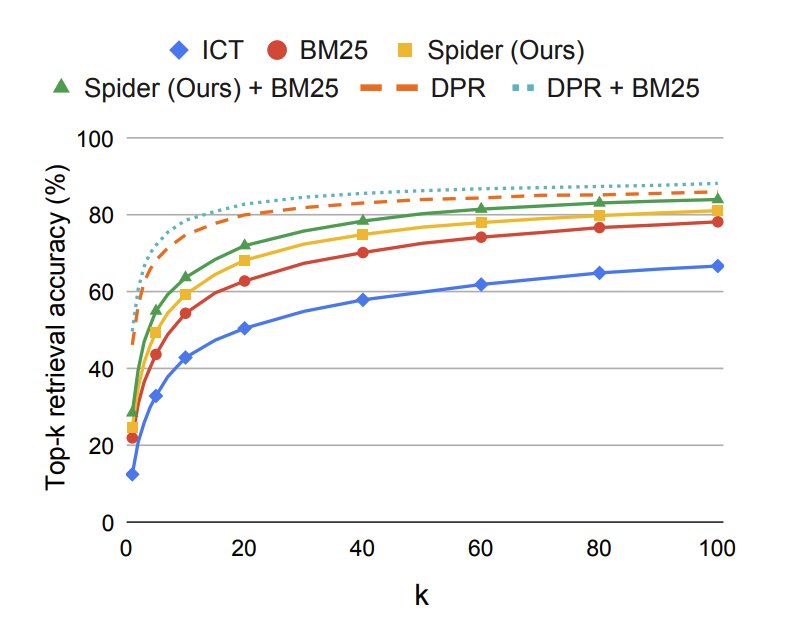

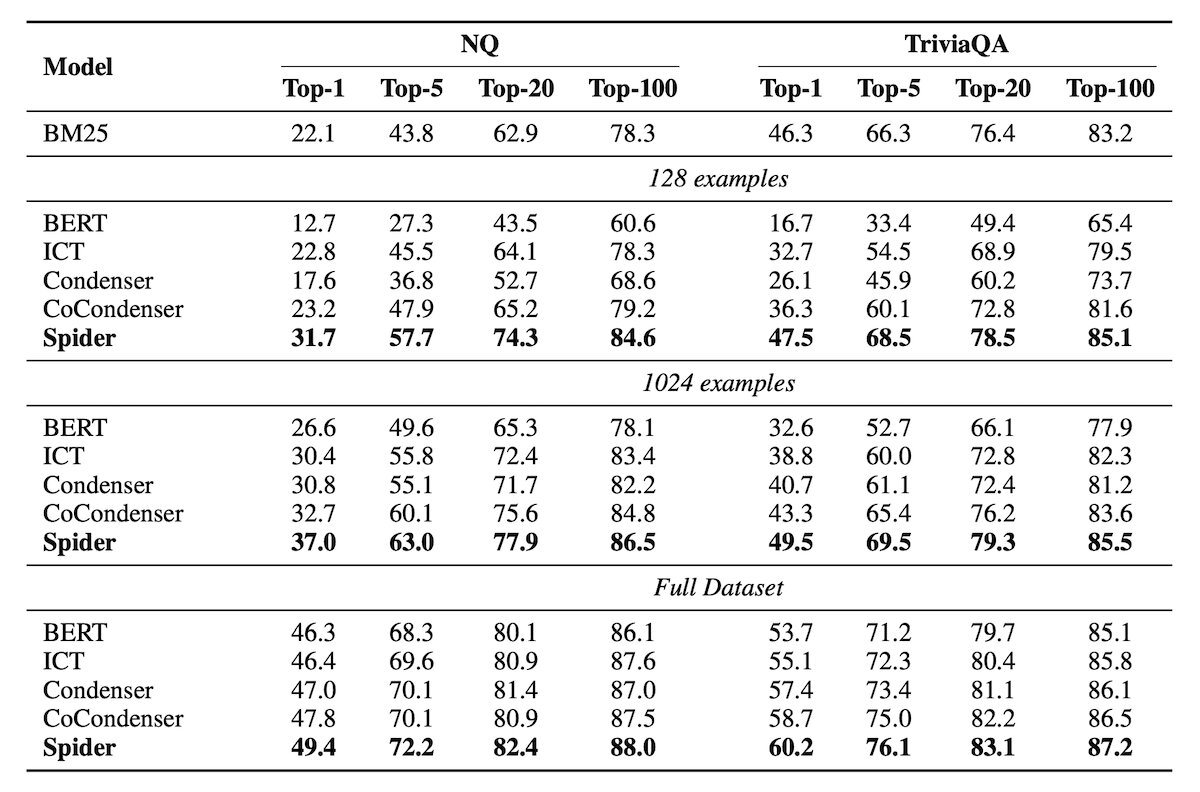

The authors experimentally present the effectiveness of Spider with the use of ODQA (Open-Domain Question Answering) datasets. ODQA datasets consist of labeled (question, answer, context) tuples. For example ("What is the atomic number of oxygen?", "8", "Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8."). Retrieval models are evaluated based on whether they can retrieve this context given the question as input and a large collection of contexts represented as vectors. This is reported with the top-k retrieval accuracy, the percentage of questions for which the answer span is found in the top-k passages most similar to the query.

The Spider retrieval models are 110 million parameter BERT-base transformers, using an uncased WordPiece tokenizer. The vector representations of passages are extracted by indexing the [CLS] token, a common indexing technique describing extraction from the leftmost vector in BERT’s output matrix. Spider is trained on a Wikipedia dump from Dec. 20th, 2018 with passages of 100 words as retrieval units, totalling 21 million passages after preprocessing. Spider is trained for 200,000 steps using a batch size of 1024. This takes 2 days on 8 80GB A100 GPUs. The authors additionally explore fine-tuning Spider with Supervised Learning using 8 Quadro RTX 8000 GPUs.

Spider + BM25 is on par with Supervised DPR when evaluated on the Supervised DPR test set!

The results of this paper are extremely exciting for Self-Supervised text retrieval! As a quick primer, Supervised text retrieval is annotated by showing a passage to a labeler, then the labeler produces a question-answer pair from the passage. The system is then trained to align the question with the passage in the same Contrastive Learning framework we have described. Supervised Learning models are typically evaluated by dividing the dataset into train-test splits. Spider (especially when boosted in a Hybrid Search framework alongside BM25) is on par with Supervised DPR when evaluated on the held-out DPR test set!

This is an absolutely amazing result and testimony to the excitement of Self-Supervised Learning methods! Who knows how much further we can take the performance of Spider since we are no longer limited by manual labeling costs? Thus, further investment in model size, unlabeled dataset size, and training time will likely yield even further improvements. The core graphic comparing Spider with Hybrid Retrieval Spider + BM25, DPR, Hybrid Retrieval DPR + BM25, BM25, and ICT is shown below:

The exact numbers behind the visualization shown above and evaluations with Natural Questions (NQ), TriviaQA, and Web Questions (WQ) are presented below:

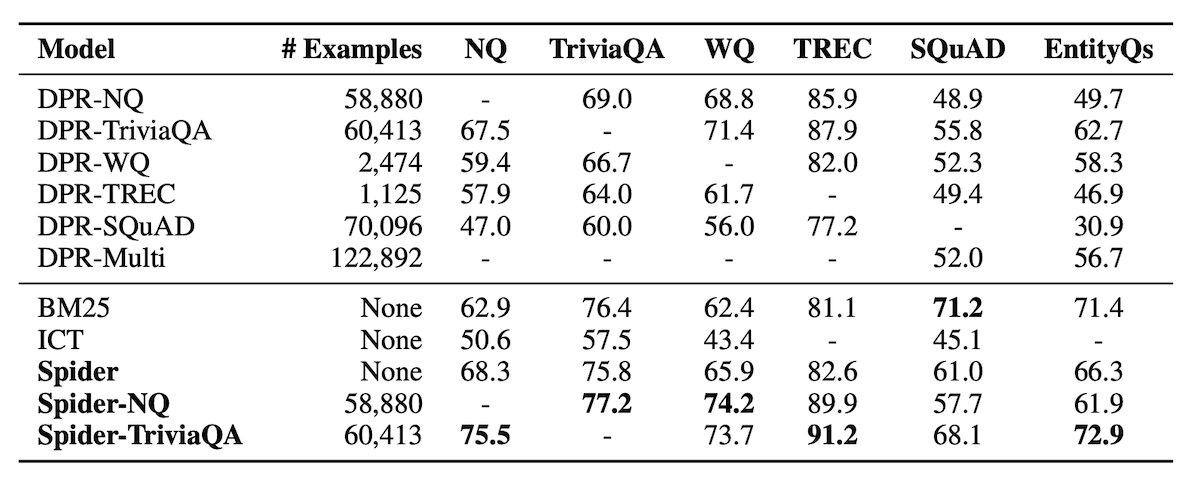

Zero-Shot Generalization

The results above look at DPR models which have been trained on the dataset they are tested on, i.e. the train-test sets are independent and identically distributed splits of the same data distribution. Another interesting measurement of these models is the Zero-Shot Generalization ability - how well these models can perform on data distributions they were not trained on.

Shown below, the Spider models have a much better Zero-Shot Generalization than the Supervised DPR models. The generalization of Supervised Learning is very limited to the training data distribution. In contrast, Self-Supervised Learning techniques such as Spider are more robust to esoteric details of questions such as the style or length. This is of course in addition to the general content such as biomedical text versus legal text.

Supervised Fine-Tuning of Spider

Perhaps more practically is to use Spider in tandem with Supervised Learning. Again, the general procedure for labeling datasets like this is to (1) show a labeler some context, like a passage and then (2) have the labeler derive a question/answer pair from the context. The training dataset is then to align questions with the originally presented passage.

An interesting question with this approach is: How many questions do we need to label? Spider further provides a benefit here, greatly reducing the number of examples needed for strong Transfer Learning performance. As described by the Ram et al., "Spider fine-tuned on 128 examples is able to outperform all other baselines when they are trained on 1024 examples". The image below presents the results of Supervised Fine-tuning with 128 examples, 1024 examples, and the full dataset.

Similar Techniques

The authors present an excellent description of experimental baselines which we encourage readers to explore. These include BM25, BERT, ICT, Condenser, CoCondenser, MSS, Contriever, and DPR.

Reflections

It is extremely exciting to see advances in Self-Supervised Learning for retrieval. This enables us to utilize larger datasets to train larger models. Further, this algorithm shows that there is plenty of opportunity on the task construction side of Self-Supervised Learning. These experiments show that how we sample positive and negative pairs is crucial for the resulting performance of the models.

We may be able to improve this further by looking at the structure of how Documents are sourced in batches. The current Spider algorithm may sample completely unrelated articles such as "Oxygen" and "LeBron James", but we can imagine isolating a set of article titles that are semantically similar. This would provide even more semantic signal in the negatives used to optimize the model. It is interesting to think of how we would source a Document batch sampling like this – the easiest way would probably be to sample a single article and then use a semantic similarity search from a zero-shot embedding model. We might also be able to exploit the ontology structure present in some datasets like Wikidata / Wikipedia.

This is very interesting for those looking to train a custom retrieval model for their search applications. We now have an established technique to Self-Supervised this training that goes beyond simple heuristics like using neighboring passages as positives. Hopefully we will see more and more people doing this and populating the HuggingFace model hub with retrieval checkpoints!

It is also very interesting to see the improvement of pairing Spider with BM25, another testimony to the effectiveness of Hybrid (Dense / Sparse) retrieval techniques. On a similar note, the ODQA evaluation suite seemed fairly comprehensive. However, it may be worth further digging into how this performs on benchmarks such as BEIR.

It is also very exciting to think about the generality of this algorithm. We could imagine applying this to code snippets, as well as DNA sequences and molecular structures. We could apply the exact same technique to code, looking for recurring spans across say a GitHub repository, or maybe even one long program. DNA sequences are a very interesting example of this as well as shared "ACCGTCCG" spans may signal a shared functional / semantic similarity. Molecular structures are also made of sub-structures in which recurrence across molecules could be a positive signal of semantic similarity. I think that this will be very useful for discrete data like text, code, base pair sequences, or molecular structures. I do not think this heuristic will be as effective for continuous data like images or audio.

Although not tested in the paper, these top-k searches can further leverage Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) indexes such as HNSW to achieve polylogarithmic scaling with respect to search time and the number of total documents. This is a very important detail for practical engineering of billion-scale similarity search.

Custom Retrievers in Weaviate

Advances such as Spider can be added to the Weaviate vector database by creating a custom module. The authors have open-sourced their model and published the weights on the HuggingFace model hub. Weaviate has a tight integration with HuggingFace in examples such as the nearText module. This enables users to change the path in their Weaviate docker image to access different HuggingFace models.

Conclusion

In conclusion, methods like Spider give Weaviate users the ability to have a customized retriever without needing to label data. Performance can be improved by labeling data, but the amount needed is greatly reduced. For the development of Weaviate, we are on the hunt for new techniques in retrieval models like this to understand advances in Search technology. We hope this article inspired your interest in Self-Supervised retrieval and emerging technologies around this!

Ready to start building?

Check out the Quickstart tutorial, or build amazing apps with a free trial of Weaviate Cloud (WCD).

Don't want to miss another blog post?

Sign up for our bi-weekly newsletter to stay updated!

By submitting, I agree to the Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.