In this blog we discuss:

- How LLMs can generate magically realistic language when prompted

- Question whether they actually understand the content they’ve read in the way humans understand

- Touch on some of the recent improvements and limitations of LLMs

ChatGPT: Catching Lightning in a Bottle ⚡

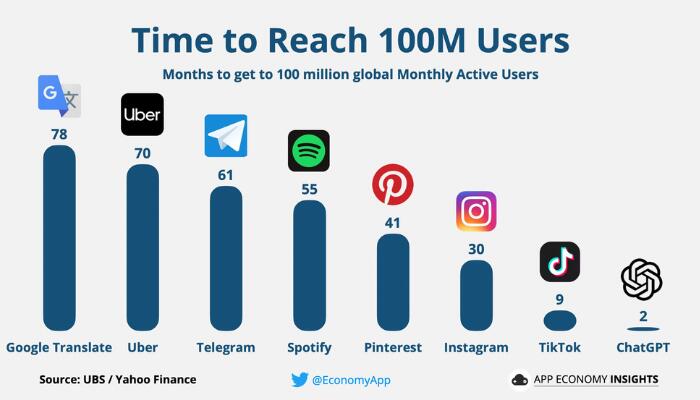

When OpenAI launched ChatGPT at the end of 2022, more than one million people had tried the model in just a week and that trend has only continued with monthly active users for the chatbot service reaching over 100 Million, quicker than any service before, as reported by Reuters and Yahoo Finance. Since then, OpenAI has been iteratively improving the underlying model, announcing the release of GPT (Generative Pretrained Transformer) 4.0 last week, with new and improved capabilities. It wouldn’t be hyperbole to say that Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Generative Large Language Models (LLMs) have taken the world by storm.

Though ChatGPT was not the first AI chatbot that has been released to the public, what really surprised people about this particular service was the breadth and depth of knowledge it had and its ability to articulate that knowledge with human-like responses. Aside from this, the generative aspect of this model is also quite apparent as it can hallucinate situations and dream up vivid details to fill in descriptions when prompted to do so. This gives the chatbot service somewhat of a human-like “creativity” - which is what adds a whole new dimension of utility for the service, as well as a wow factor to the user experience!

In fact, a huge reason why these models are fascinating is because of their ability to paraphrase and articulate a vast general knowledge base by generating human-like phrases and language. If ChatGPT had simply “copy-pasted” content from the most relevant source to answer our questions, it would be far less impressive a technology. In the case of language models, their ability to summarize, paraphrase and compress source knowledge into realistic language is much more impressive. Ted Chiang captures this exact concept eloquently in his recent article ChatGPT Is a Blurry JPEG of the Web.

In this blog, I’ll attempt to explain the intuition of how these models generate realistic language by providing a gentle introduction to their underlying mechanisms. We’ll keep it very high level so that even if you don’t have a background in machine learning or the underlying mathematics, you’ll understand what they can and cannot do.

What Are LLMs? - Simply Explained

I like to think of large language models as voracious readers 👓📚: they love to read anything and everything they can get their hands on. From cooking recipes to Tupac rap lyrics, from car engine manuals to Shakespeare poetry, from Manga to source code. Anything you can imagine that is publicly available to be read, LLMs have read. Just to give you an idea, GPT 3.0 was trained on 500+ billion words crawled from Wikipedia, literature, and the internet. Think of it this way: LLMs have already read anything you can google and learn. The fact that LLMs have read all of this material is what forms their vast knowledge base.

This explains why LLMs know something about basically everything but it still doesn’t explain how they articulate this knowledge with human-like responses. The question then arises, what is the point of all this reading!? Are LLMs trying to comprehend what’s being read? Are they trying to break apart and learn the logic behind the concepts they are reading so they can piece back together concepts on demand upon questioning - as a student preparing for an exam would? Perhaps, but not quite in the way that humans learn and understand from reading. The answer to these questions lies in their name: “Language Model”. LLMs are trying to build a statistical model of the language they are reading.

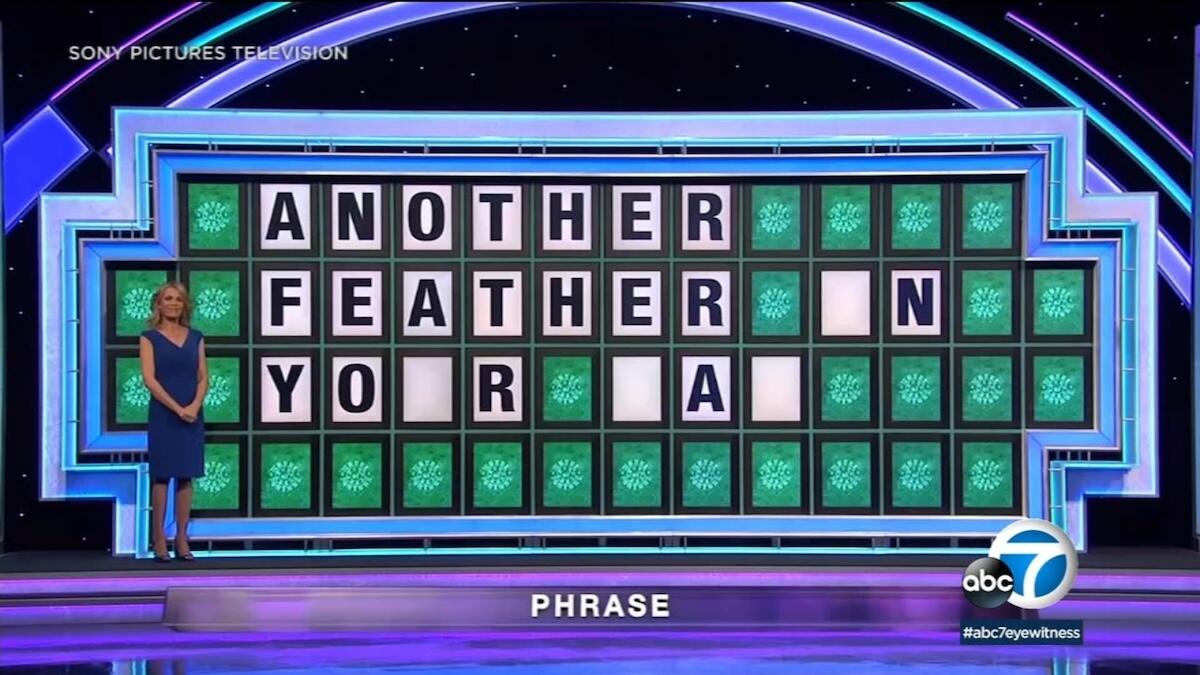

To understand how LLMs work let's consider a scenario. Imagine you are on the Wheel of Fortune game show and are tasked with completing the following phrase:

The vast majority of you, I bet, would answer: "EASY! It’s: 'ANOTHER FEATHER IN YOUR CAP'." And you would be correct! But humor me for a second while I play devil’s advocate and propose an alternative: Why not: “ANOTHER FEATHER ON YOUR CAT”? This is a perfectly structured and complete English sentence. Why, then, did no one think of this alternative as a potential completion of the phrase?

Humans can reason and understand language at increasingly deeper levels of meaning. Here are some reasons, in order of increasing lingual comprehension, that explains why the latter phrase didn’t occur to many:

You’ve heard the former phrase before, whereas you’ve never heard the latter; one combination of words is common and familiar, while the other is not.

You know that feathers can go in caps, however feathers don’t go on cats! Even on a superficial level, one makes sense based on our understanding and knowledge of the world, and the other does not!

You can understand the deeper meaning behind the prior phrase as accomplishing something to be proud of, whereas the latter doesn’t have any deeper meaning behind it.

If there were a deeper meaning to be interpreted, such as irony or sarcasm that was subtley woven into the phrase, humans would also be able to comprehend that.

The question then arises...

Do LLMs Actually Understand What They Read?

The above scenario is an example of the statistical model and understanding of language that humans possess. Humans are great at understanding and constructing a statistical model of our mother tongues or languages that we’ve been trained in. So good, in fact, that we can use this model implicitly on demand without even realizing the multiple levels of comprehension we’re considering when completing the phrase - it becomes second nature to us.

At a high level, this is what LLMs like OpenAI’s GPT 4.0, Meta’s LLaMA, and Google’s LaMDA are trying to achieve from their vast amounts of reading. They are trying to measure which words are often used together across different types of texts. This allows them to quantify which combination of words and phrases are common and which ones aren’t - allowing them to emulate the first level of reasoning above.

Furthermore, by putting together knowledge of commonly occurring words, they can also learn higher level concepts (such as relationships between words), to learn that feathers can go in caps but they don’t go on cats - and reach the second point above.

The state-of-the-art LLMs such as GPT 4.0 can even abstract away and quantify that you’re not actually referring to feathers and caps when you say “ANOTHER FEATHER IN YOUR CAP” since they have read this exact phrase used in context before! This gets them partially to the third point we mentioned above.

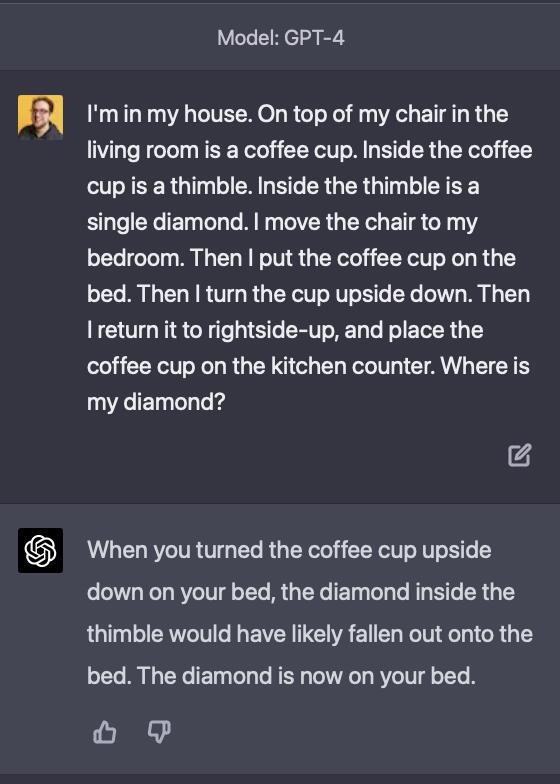

One current limitation of LLMs, which can prevent them from attaining points 3 and 4 reliably, and is actively being worked on, is how far these features and interactions can penetrate into deeper meanings of language, to follow logic and use a world model to understand and follow a sequence of actions. GPT 4.0 shows great strides forward compared to GPT 3.5 in this domain, as demonstrated by Daniel Feldman's prompting shared below:

| GPT 3.5 | GPT 4.0 |

|---|---|

|  |

These LLMs are distilling the information they read from vast amounts of interactions between words. So both humans and LLMs in their unique ways build a statistical understanding of the language they are trained on.

As Geoff Hinton, sometimes referred to as the “Godfather of Deep Learning”, recently put it:

“LLMs do not do pattern matching in the sense that most people understand it. They use the data to create huge numbers of features and interactions between features such that these interactions can predict the next word.”

These features are preserved in the LLM’s parameters (what I like to think of as the brains of the model), which GPT 3.0 has 175 billion of - it would require 800GB to even store these parameters. Now whether you consider passing a prompt through these parameters and getting an LLM to generate the most likely response word by word as requiring an “understanding” of the underlying text in the same way that a human would “understand” a question prior to formulating an answer, is an open question that I leave to the reader to ponder!

Geoff has another great take on this:

“I believe that factoring the discrete symbolic information into a very large number of features and interactions IS intuitive understanding and that this is true for both brains and LLMs even though they may use different learning algorithms for arriving at these factorizations.”

Another limitation of these models, to keep in mind when thinking about whether LLMs understand what they read, is that they are only “language” models whereas humans have the benefit of putting together and choosing between multiple modalities of understanding, including language, visual, aural, mathematical, physical etc. An example of this is that LLMs are not good at solving mathematical problems since they cannot distill and learn the rules of algebra from reading a math textbook - they don’t have a “math mode” that overrides their “language mode” when tasked with solving even the easiest of math problems. So it’s really not fair to compare an LLM’s uni-modal comprehension to that of a humans full multi-modal comprehension capabilities. Efforts are being made to make these models understand other modalities of data - for example with the release of GPT 4.0 last week, ChatGPT can now understand images that you pass in and can couple this image understanding with its language understanding.

Conclusions

In this post we dove into a plain English explanation of what LLMs are, how they work and what they are "learning" that allows them to approximate human language with such prowess! If you enjoy plain and simple explanations of machine learning concepts that are revolutionizing our everyday lives, keep an eye out on our blog page - we've got lots more coming!

Ready to start building?

Check out the Quickstart tutorial, or build amazing apps with a free trial of Weaviate Cloud (WCD).

Don't want to miss another blog post?

Sign up for our bi-weekly newsletter to stay updated!

By submitting, I agree to the Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.