The recent breakthroughs in Large Language Model (LLM) technology are positioned to transition many areas of software. Search and Database technologies particularly have an interesting entanglement with LLMs. There are cases where Search improves the capabilities of LLMs as well as where inversely, LLMs improve the capabilities of Search. In this blog post, we will break down 5 key components of the intersection between LLMs and Search.

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation

- Query Understanding

- Index Construction

- LLMs in Re-Ranking

- Search Result Compression

We will also conclude with some thoughts on how Generative Feedback Loops fit into this picture.

Retrieval-Augmented Generation

Since the inception of large language models (LLMs), developers and researchers have tested the capabilities of combining information retrieval and text generation. By augmenting the LLM with a search engine, we no longer need to fine-tune the LLM to reason about our particular data.This method is known as Retrieval-augmented Generation (RAG).

Without RAG, an LLM is only as smart as the data it was trained on. Meaning, LLMs can only generate text based purely on what its “seen”, rather than pull in new information after the training cut-off. Sam Altman stated “the right way to think of the models that we create is a reasoning engine, not a fact database.” Essentially, we should only use the language model for its reasoning ability, not for the knowledge it has.

RAG offers 4 primary benefits over traditional language modeling:

- It enables the language model to reason about new data without gradient descent optimization.

- It is easier to update the information.

- It is easier to attribute what the generation is based on (also known as “citing its sources”) and helps with hallucination.

- It reduces the parameter count needed to reason. Parameter count is what makes these models expensive and impractical for some use cases (shown in Atlas).

How LLMs send Search Queries

Let’s dig a little deeper into how prompts are transformed into search queries. The traditional approach is simply to use the prompt itself as a query. With the innovations in semantic vector search, we can send less formulated queries like this to search engines. For example, we can find information about “the eiffel tower” by searching for “landmarks in France”.

However, sometimes we may find a better search result by formulating a question rather than sending a raw prompt. This is often done by prompting the language model to extract or formulate a question based on the prompt and then send that question to the search engine, i.e. “landmarks in France” translated to, “What are the landmarks in France?”. Or a user prompt like “Please write me a poem about landmarks in France” translated to, “What are the landmarks in France?” to send to the search engine.

We also may want to prompt the language model to formulate search queries as it sees fit. One solution to this is to prompt the model with a description of the search engine tool and how to use it with a special [SEARCH] token. We then parse the output from the language model into a search query. Prompting the model to trigger a [SEARCH] is also handy in the case of complex questions that often need to be decomposed into sub-questions. LlamaIndex has this feature implemented in their framework called the sub question query engine. It takes complex queries, breaks it down into sub-questions using multiple data sources and then gathers the responses to form the final answer.

Another interesting technique is to trigger additional queries based on the certainty of the language model’s output. As a quick reminder, Language Models are probability models that assign probabilities to the most likely word to continue a sequence of text. The FLARE technique samples a potential next sentence, multiplies the probabilities of each word, and if it is below a certain threshold, triggers a search query with the previous context. More info about the FLARE technique can be found here.

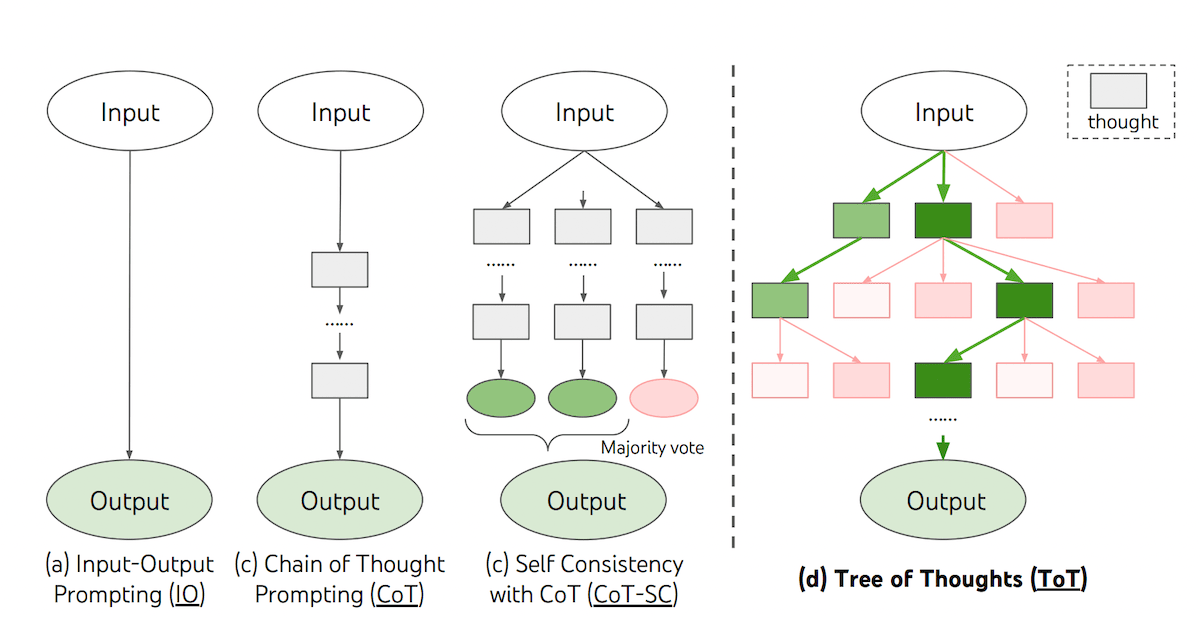

Some queries require a very thorough search or need to be refined. Chain of thought is a method commonly used to assist the language model with its reasoning capability. AutoGPT demonstrated how a model could run autonomously to complete various tasks without much human intervention. This was done by using chain of thought reasoning to break down tasks into intermediate steps. The program would then run continuously until all tasks were completed.

Another cutting edge idea in this line of thinking is Tree-of-Thoughts sampling. In a Tree-of-Thoughts search, each node represents a prompt to the language model. We then branch the tree by sampling multiple stochastic generations. The algorithm is coupled with a decision making node that determines which branches to cut or when a satisfactory answer has been discovered. An illustration of Tree-of-Thoughts from Yao et al. is presented below:

Query Understanding

Rather than blindly sending a query to the search engine, Vector Databases, such as Weaviate, come with many levers to pull to achieve better search results. Firstly, a query may be better suited for a symbolic aggregation, rather than a semantic search. For example: “What is the average age of country music singers in the United States of America?”. This query is better answered with the SQL query: SELECT avg(age) FROM singers WHERE genre=”country” AND origin=”United States of America”.

In order to bridge this gap, LLMs can be prompted to translate these kinds of questions into SQL statements which can then be executed against a database. Similarly, Weaviate has an Aggregate API that can be used for these kinds of queries on symbolic metadata associated with unstructured data.

In addition to the Text-to-SQL topic, there are also knobs to turn with vector search. The first of which being, Which Class do we want to search through? In Weaviate, we have the option to divide our data into separate Classes in which each Class has a separate Vector Index, as well as a unique set of symbolic properties. Which brings us to the next decision when vector searching: Which Filters do we want to add to the search? A great example of this is filtering search results based on price. We don’t just want the items with the most semantic similarity to the query, but also those that are less than $100. LlamaIndex’s Query Engine presents really nice abstractions to leverage this concept of LLM Query Understanding.

In the following illustration, the LLM adds the filter, where “animal” = “dog” to facilitate searching for information about Goldendoodles. This is done by prompting the LLM with information about the data schema and the syntax for formatting structured vector searches in Weaviate.

Index Construction

Large Language Models can also completely change the way we index data for search engines, resulting in better search quality down the line. There are 4 key areas to consider here:

- Summarization indexes

- Extracting structured data

- Text chunking

- Managing document updates.

Summarization Indexes

Vector embedding models are typically limited to 512 tokens at a time. This limits the application of vector embeddings to represent long documents such as an entire chapter of a book, or the book itself. An emerging solution is to apply summarization chains such as the create-and-refine example animated at the end of this article to summarize long documents. We then take the summary, vectorize it, and build an index to apply semantic search to the comparison of long documents such as books or podcast transcripts.

Extracting Structured Data

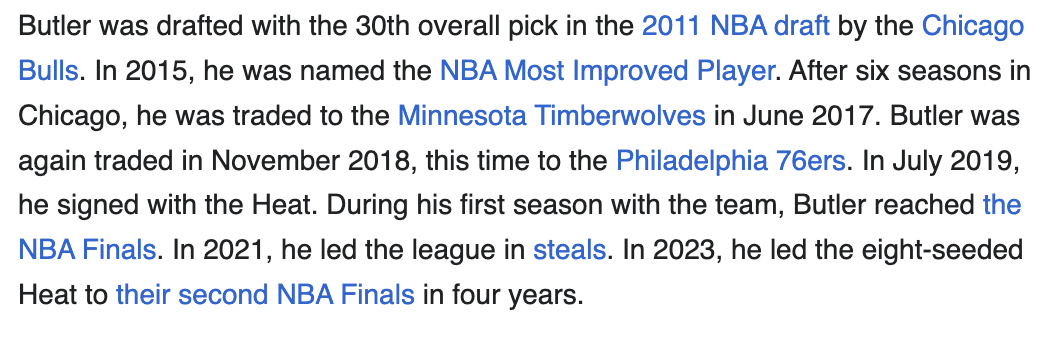

The next application of LLMs in Search Index Construction is in extracting structured data from unstructured text chunks. Suppose we have the following text chunk extracted from the Wikipedia page of Jimmy Butler from the Miami Heat:

Now we prompt the Large Language Model as follows:

Given the following text chunk: `{text_chunk}`

Please identify any potential symbolic data contained in the passage. Please format this data as a json dictionary with the key equal to the name of the variable and the value equal to the value this variable holds as evidenced by the text chunk. The values for these variables should either have `int`, `boolean`, or `categorical` values.

For this example, text-davinci-003 with temperature = 0 produces the following output:

{ "Draft Pick": 30, "Most Improved Player": true, "Teams": ["Chicago Bulls", "Minnesota Timberwolves", "Philadelphia 76ers", "Miami Heat"], "NBA Finals": 2, "Lead League in Steals": true }

We can apply this prompt to each chunk of text in the Wikipedia article and then aggregate the symbolic properties discovered. We can then answer symbolic questions about our data such as, How many NBA players have played for more than 3 distinct NBA teams?. We can also use these filters for vector search as described above with respect to the Llama Index Query Engine.

Symbolic Data to Text

Prior to the emergence of LLMs, most of the world’s data has been organized in tabular datasets. Tabular datasets described the combination of numeric, boolean, and categorical variables. For example, “age” = 26 (numeric), “smoker” = True (boolean), or “favorite_sport” = “basketball” (categorical). An exciting emerging technique is to prompt a large language model to translate tabular data into text. We can then vectorize this text description using off-the-shelf models from OpenAI, Cohere, HuggingFace, and others to unlock semantic search. We recently presented an example of this idea for AirBnB listings, translating tabular data about each property’s price, neighborhood, and more into a text description. Huge thanks to Svitlana Smolianova for creating the following animation of the concept.

Text Chunking

Similarly related to the 512 token length for vectorizing text chunks, we may consider using the Large Language Model to identify good places to cut up text chunks. For example, if we have a list of items, it might not be best practice to separate the list into 2 chunks because the first half fell into the tail end of a chunk[:512] loop. This is also similar to prompts to automatically identify the key topics in a long sequence of text such as a podcast, youtube video, or article.

Managing Document Updates

Another emerging problem LLMs are solving in this space is the continual maintenance of a search index. Perhaps the best example of this is code repositories. Oftentimes a pull request may completely change a block of code that has been vectorized and added to the search index. We can prompt LLMs by asking, is this change enough to trigger a re-vectorization? Should we update the symbolic properties associated with this chunk? Should we reconsider the chunking around the context because of this update? Further, if we are adding a summarization of the larger context into the representation of this chunk, is this a significant enough update to re-trigger summarizing the entire file?

LLMs in Re-Ranking

Search typically operates in pipelines, a common term to describe directed acyclic graph (DAG) computation. As discussed previously, Query Understanding is the first step in this pipeline, typically followed by retrieval and re-ranking.

As described in our previous article, re-ranking models are new to the scene of zero-shot generalization. The story of re-rankers has mostly been tabular user features combined with tabular product or item features, fed to XGBoost models. This required a significant amount of user data to achieve, which zero-shot generalization may stand to disrupt.

Cross encoders have gained popularity by taking as input a (query, document) pair and outputting a high precision relevance score. This can be easily generalized to recommendation as well, in which the ranker takes as input a (user description, item description) pair.

LLM Re-Rankers stand to transform Cross Encoders by taking in more than one document for this high precision relevance calculation. This enables the transformer LLM to apply attention over the entire list of potential results. This is also heavily related to the concept of AutoCut with LLMs, this refers to giving the Language Model k search results and prompting it to determine how many of the k search results are relevant enough to either show to a human user, or pass along the next step of an LLM computation chain.

Returning to the topic of XGBoost symbolic re-ranking, LLM re-rankers are also quite well-positioned to achieve innovations in symbolic re-ranking as well. For example, we can prompt the language model like this:

Please rank the following search results according to their relevance with the query: {query}.

Please boost relevance based on recency and if the Author is “Connor Shorten”.

Each search result then comes packaged with their associated metadata in a key-value array. This offers the additional benefit of allowing business practitioners to easily swap out the ranking logic. This also holds the benefit of dramatically increasing the interpretability of recommendation systems, since LLMs can easily be prompted to provide an explanation of the ranking in addition to the ranking itself.

Search Result Compression

Traditionally, search results are presented to human users as a long list of relevant websites or passages. This then requires additional effort to sift through the results to find the desired information. How can new technologies reduce this additional effort? We will look at this through the lens of (1) question answering and (2) summarization.

Question Answering

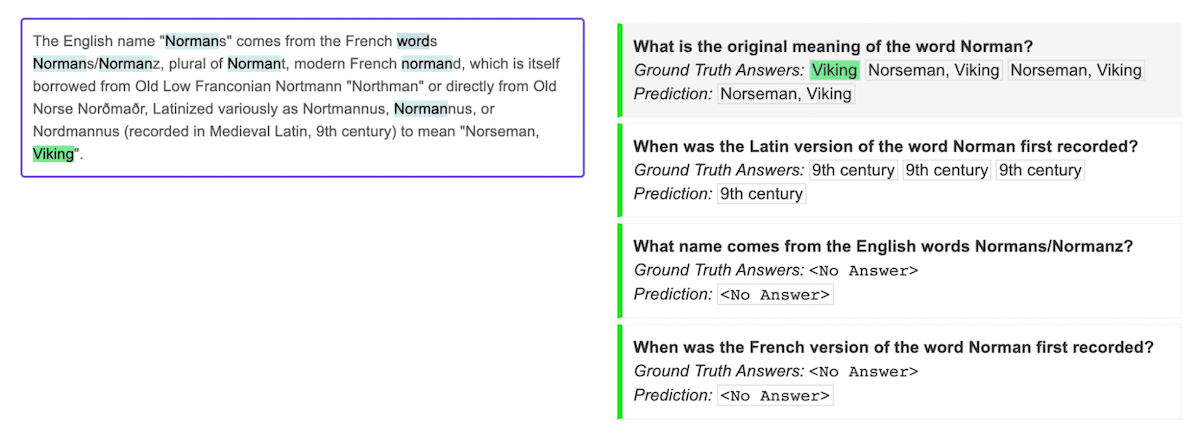

Even prior to the recent breakthroughs in LLMs, extractive question answering models were beginning to innovate on this experience. Extractive question answering describes the task of classifying the most likely answer span given a question and text passage as input. Similar to the ability of ChatGPT to reason about your data without costly training on it, many off the shelf extractive question answering models can generalize quite well to new (question, text passage) pairs not seen during training. An example of this is shown below:

One benefit of Extractive QA is that there is no chance of Hallucination. Hallucination, where Machine Learning models make up information in their responses, is impossible with this kind of technique because it is completely limited by the input context. That’s not to say that it can’t be incorrect in its answer. However, on the flip side of that is that these models are limited by the context and thus unable to reason about complex questions and combine parts of answers assembled across the passage. So unless we have a question as straightforward as “What is the original meaning of the word Norman?”, LLMs offer a significant new capability.

Another key component to this is the ability of LLMs to assemble parts of information across several passages. For example, we can apply a Map Reduce prompt such as:

Please summarize any information in the search result that may help answer the question: {query}

Search result: {search_result}

And then assemble these intermediate responses from each passage with:

Please answer the following question: {query} based on the following information {information}

Maybe we can imagine applying the “reduce” half of the “map reduce” prompt to information extracted from extractive classifiers on each passage. This may be a cheaper approach to the “map” step, but it is unlikely to work as well and doesn’t offer the same flexibility in changing what the “map” prompt extracts from each passage.

Summarization

Similar to Question Answering with LLMs, when we consider multiple passages longer than 512 tokens compared to a single passage, Summarization with LLMs offers a significant new ability for AI systems.

Please summarize the search results for the given query: {query}

You will receive each search result one at a time, as well as the summary you have generated so far.

Current summary: {current_summary}

Next Search Result: {search_result}

Recap of Key Ideas

Here is a quick recap of the key concepts we have presented at the intersection of Large Language Models and Search:

- Retrieval-Augmented Generation: Augmenting inputs to LLMs by retrieving extra information from a search engine. There is growing nuance in how exactly this retriever is triggered, such as Self-Ask prompting or FLARE decoding.

- Query Understanding: LLMs can reliably translate natural language questions into SQL for symbolic aggregations. This technique can also be used to navigate Weaviate by choosing, which

Classto search as well as whichfiltersto add to the search. - Index Construction: LLMs can transform information to facilitate building search indexes. This can range from summarizing long content to extracting structured data, identifying text chunks, managing document updates, or transformation structured data to text for vectorization.

- LLMs in Re-Ranking: Ranking models, distinctly from Retrieval, explicitly takes the query and/or a user description, as well as each candidate document as input to the neural network to output a fine-grained score of relevance. LLMs can now do this off-the-shelf without any extra training. Quite interestingly, we can prompt the LLMs to rank with symbolic preferences such as “price” or “recency”, in addition to the unstructured text content.

- Search Result Compression: LLMs are delivering new search experiences for human users. Rather than needing to browse through search results, LLMs can apply map reduce or summarization chains to parse 100s of search results and show humans, or other LLMs, a much denser end result.

Generative Feedback Loops

In our first blog post on Generative Feedback Loops, we shared an example on how to generate personalized ads for AirBnB listings. It takes the users preferences and finds relevant listings that would be of interest to them. The language model then generates an ad for the listings and links it back to the database with a cross-reference. This is interesting because we are using outputs from the language model and indexing the results to retrieve later.

Generative Feedback Loops is a term we are developing to broadly reference cases where the output of an LLM inference is saved back into the database for future use. This blog post has touched on a few cases of this such as writing a summary of a podcast and saving the result back to the database, as well as extracting structured data from unstructured data to save back in the database.

Commentary on LLM Frameworks

LLM Frameworks, such as LlamaIndex and LangChain, serve to control the chaos of emerging LLM applications with common abstractions across projects. We want to conclude the article with a huge thank you to the builders of these frameworks which have greatly helped our understanding of the space. Another major thank you to Greg Kamradt and Colin Harmon for the discussion of these topics on Weaviate Podcast #51.

Ready to start building?

Check out the Quickstart tutorial, or build amazing apps with a free trial of Weaviate Cloud (WCD).

Don't want to miss another blog post?

Sign up for our bi-weekly newsletter to stay updated!

By submitting, I agree to the Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.